[Archived] Attachment Security and Disorganization in Maltreating Families and Orphanages

Marinus H. van IJzendoorn, PhD, Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg, PhD

Centre for Child and Family Studies, Leiden University, Netherlands

Introduction

Extremely insensitive and maltreating caregiving behaviors may be among the most important precursors involved in the development of attachment insecurity and disorganization. Egeland and Sroufe1 pointed out the dramatically negative impact of neglecting or abusive maternal behavior for attachment and personality development, for which they accumulated unique prospective evidence in later phases of the Minnesota study.2 What do we know about the association between child maltreatment and attachment, what are the mechanisms linking maltreatment with attachment insecurity and disorganization, and what type of attachment-based interventions might be most effective?

Subject

Following Cicchetti and Valentino,3 we include in our definition of child maltreatment sexual abuse,physical abuse,neglect and emotional maltreatment. Besides these “family-context” types of maltreatment, we also draw attention to structural neglect from which world-wide millions of orphans and abandoned children suffer. Structural neglect points to the inherent features of institutional care that preclude continuous, stable and sensitive caregiving for individual children: caregiver shifts, high staff-turnover rates, large groups, strict regimes, and sometimes physical and social chaos.4

Attachment disorganization has been suggested to be caused by frightening and extremely insensitive or neglectful caregiving.5 Studies on non-maltreated samples have demonstrated that anomalous parenting, involving (often only brief episodes of) parental dissociative behavior, rough handling, or withdrawn behavior, is related to the development of attachment disorganization (see Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg et al.,6 for a meta-analytic review). Parental maltreatment is probably one of the most frightening behaviors a child may be exposed to. Abusive mothers show aversive, intrusive and controlling behavior toward their child, in contrast to neglecting mothers who may display inconsistent care. Maltreating insensitive parents do not regulate or buffer their child’s experience of distress, but they also activate their child’s fear and attachment systems at the same time. The resulting experience of fright without solution is characteristic of maltreated children. According to Hesse and Main,5 disorganized children are caught in an unsolvable paradox: their attachment figure is a potential source of comfort and at the same time a source of unpredictable fright.

Problems

We speculate that multiple pathways to attachment disorganization exist involving either child maltreatment by abusive parents or neglect in chaotic multiple-risk families or institutions.

The pathway of abuse is based on the idea of (physically or sexually) maltreating parents creating fright without solution for the child who cannot handle the paradox of a potentially protective and, at the same time, abusive attachment figure, and thus becomes disorganized.

A second pathway is associated with the chaotic environment of multiple-risk families or institutional care leading to neglect of the attachment needs of the children. Caregivers’ withdrawal from interacting with the children because of urgent problems and hassles in other domains of functioning (securing an income, housing problems, too many children to care for) creates a chronic hyper-aroused attachment system in a child who does not know to whom to turn for consolation in times of stress. This may in the end lead to a breakdown of organized attachment strategies or impede children’s capacity to even develop an organized insecure attachment strategy.

Third, marital discord and domestic violence may lead to elevated levels of disorganization as the child is witnessing an attachment figure unable to protect herself in her struggle with a partner. Zeanah et al.7 documented a dose-response relation between mothers’ exposure to partner violence and infant disorganization. Witnessing parental violence may elicit fear in a young child about the mother’s well-being and her ability to protect herself and the child against violence.

Research Context

Collecting data on maltreatment samples is difficult. Maltreated children are often victims of multiple forms of abuse, making it difficult to compare the different types of maltreatment. Conjoint work with the child welfare system may raise legal and ethical issues involving sharing information with clinical workers or being asked to provide a statement in court.

Remarkable and rigorous but scarce work has been conducted by research groups pioneering this challenging area. Seven studies on attachment security/disorganization and child maltreatment in families have been reported, and six studies on attachment in institution-reared children using the (modified) Strange Situation procedure to assess attachment.8 In order to examine the impact of child maltreatment on attachment we compare the studies’ combined distribution of attachment patterns to the normative low-risk distribution of attachment (N=2104, derived from the meta-analysis of Van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg8): insecure-avoidant (A): 15%, secure (B): 62%, insecure-resistant (C): 9%, and disorganized (D): 15%.

Key Research Questions

Three issues are central: first, does child maltreatment lead to more insecure-organized (avoidant and resistant) attachments? Second, is maltreatment related to attachment disorganization? Third, what are effective (preventive) interventions for child maltreatment?

Recent Research Results

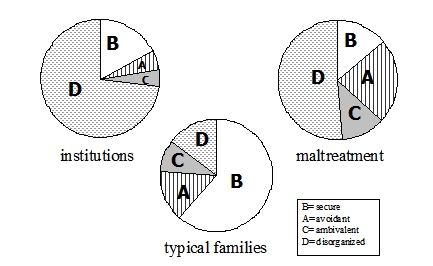

Studies of children maltreated in families show very few securely-attached children (14%), a majority of disorganized children (51%), and some insecure-avoidant (23%) and insecure-resistant (12%) attachments. This distribution differs strongly from the normative distribution, in particular in terms of disorganization10,11,1,12,13,14 (for a meta-analysis see Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn15).

Six recent studies addressed the effects of institutional care on attachment.16,17,18,19,20,21 Overall, the distribution of institution-reared children was strongly deviating from the norm distribution, with 17% secure, 5% avoidant, 5% resistant, and 73% disorganized attachments to the favorite caregiver.

The percentage of secure attachments is similar in maltreated children and institution-reared children, but the percentage of disorganized attachments in institution-reared children is considerably larger (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Attachment Distributions (Proportions) in Maltreatment Samples, Institutions and Typical Families

Research Gaps

How do some institution-reared and maltreated children develop secure attachment, and what characterizes these children? Does attachment security constitute a protective factor in high-risk contexts? Does it interact with other protective factors such as the child’s biological constitution or the caregivers’ psychosocial resources? Little is know about the differential effects of the various types of abuse and neglect – co-morbidity may hamper a clear distinction of differential effects. Lastly, long-term effects of child maltreatment should be studied more closely.

Implications for Parents, Services and Policy

Several randomized control trials have started to provide data on the effectiveness of attachment-based interventions with high-risk populations (see Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, & Juffer22, Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van Ijzendoorn4, and Berlin, Ziv, Amaya-Jackson, & Greenberg23 for reviews). However, very few of these intervention studies were conducted with maltreated children and their parents, or with children in orphanages.

The lack of evidence-based interventions for maltreatment may have led some clinicians to rely on so-called holding therapies, in which children are forced to make physical contact with their caregiver although they strongly resist these attempts. Holding therapy has not been proven to be effective,24,25 and in some cases has been harmful for children to the level of casualties.26 Holding therapy is not implied at all by attachment theory. In fact, therapists force the caregiver to be extremely insensitive and to ignore clear child signals.

A major randomized control study by Cicchetti, Rogosch, and Toth27 has demonstrated the effectiveness of an attachment-based intervention for maltreating families with child-parent psychotherapy, enhancing maternal sensitivity through reinterpretation of past attachment experiences. The intervention resulted in a substantial reduction in infant disorganized attachment, and an increase in attachment security.

Maltreatment prevalence data show a large impact of risk factors associated with a very low education and unemployment of parents (e.g., Euser et al.28). A practical implication of this observation is the recommendation to pursue a socio-economic policy with a strong emphasis on education and employment. Since unemployed and school dropped-out parents are the most frequent perpetrators of child maltreatment, policies enhancing education and employment rates are expected to effectively decrease child maltreatment rates.

References

- Egeland B, Sroufe AL. Attachment and early maltreatment. Child Development 1981;52(1):44-52.

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins WA. The Development of the Person. The Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaptation from Birth to Adulthood. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2005.

- Cicchetti D, Valentino K. An ecological-transactional perspective on child maltreatment: Failure of the average expectable environment and its influence on child development. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, eds. Developmental Psychopathology. 2nd Ed. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons; 2006:129-201.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Earlier is better: A meta-analysis of 70 years of intervention improving cognitive development in institutionalized children. Monographs of the Society for Research of Child Development 2008;73(3):279-293.

- Hesse E, Main M. Frightened, threatening, and dissociative parental behavior in low-risk samples: Description, discussion, and interpretations. Development and Psychopathology 2006;18(2):309-343.

- Madigan S, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Moran G, Pederson DR, Benoit D. Unresolved states of mind, anomalous parental behavior, and disorganized attachment: A review and meta-analysis of a transmission gap. Attachment and Human Development 2006;8(2):89-111.

- Zeanah CH, Danis B, Hirshberg L, Benoit D, Miller D, Heller SS. Disorganized attachment associated with partner violence: A research note. Infant Mental Health Journal 1999;20(1):77-86.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1978.

- Van IJzendoorn MH, Schuengel C, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology 1999;11(2):225-249.

- Barnett D, Ganiban J, Cicchetti D. Maltreatment, negative expressivity, and the development of type D attachments from 12 to 24 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 1999;64(3):97-118.

- Crittenden PM. Relationships at risk. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, eds. Clinical Implications of Attachment. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc;1988:136-174.

- Lamb ME, Gaensbauer TJ, Malkin CM, Schultz LA. The effects of child maltreatment on security of infant-adult attachment. Infant Behavior and Development 1985;8(1):35-45.

- Lyons-Ruth K, Connell DB, Grunebaum HU, Botein, S. Infants at social risk: Maternal depression and family support services as mediators of infant development and security of attachment. Child Development 1990:61(1):85-98.

- Valenzuela M. Attachment in chronically underweight young children. Child Development 1990;61(6):1984-1996.

- Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J, Van IJzendoorn MH. Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development & Psychopathology 2010;22(1):87-108.

- The St. Petersburg – USA Orphanage Research Team. The effects of early social-emotional and relationship experience on the development of young orphanage children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 2008;73(3):1-262.

- Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Dunn J, van IJzendoorn MH, Steele H, Kontopoulou A, Sarafidou J. Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2003;44(8):1208-1220.

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Carlson E, Bucharest Early Internvention Project Core Group. Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child Development 2005;76(5):1015-1028.

- Steele M, Steele H, Jin X, Archer M, Herreros F. Effects of lessening the level of deprivation in Chinese orphanage settings: Decreasing disorganization and increasing security. Paper presented at: The Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development. April 2-4, 2009; Denver, CO.

- Herreros F. Attachment security of infants living in a Chilean orphanage. Poster session presented at: The Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development. April 2-4, 2009; Denver, CO.

- Dobrova-Krol NA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MH, van Ijzendoorn MH, Juffer J. The importance of quality of care: Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on preschoolers’ attachment and indiscriminate friendliness. In: Dobrova-Krol NA, eds. Vulnerable children in Ukraine impact of institutional care and HIV on the development of preschoolers. Leiden, the Netherland: Mostert en van Onderen; 2009.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin 2003;129(2):195-215.

- Berlin LJ, Ziv Y, Amaya-Jackson L, Greenberg MT, eds. Enhancing Early Attachments: Theory, Research, Intervention, and Policy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005.

- O’Connor MJ, Zeanah CH. Introduction to the special issue: Current perspectives on assessment and treatment of attachment disorders. Attachment & Human Development 2003;5(3):221-222.

- Sroufe A, Erickson MF, Friedrich WN. Attachment theory and “attachment therapy.” APSAC Advisor 2002;14:4-6.

- Chaffin M, Hanson R, Saunders B, Barnett D, Zeanah C, Berliner L, Egeland B, Lyon T, Letourneau E, Miller-Perrin C. Report of the APSAC Task Force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreatment 2006;11(1):76-89.

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. Fostering secure attachment in infants in maltreating families through prevention interventions. Development and Psychopathology 2006;18:623-649.

- Euser EM, Van IJzendoorn MH, Prinzie P, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. The prevalence of child maltreatment in Netherlands. Child Maltreatment 2010;15(1):5-17.

How to cite this article:

van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. [Archived] Attachment Security and Disorganization in Maltreating Families and Orphanages. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. MacMillan HL, topic ed. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/maltreatment-child/according-experts/attachment-security-and-disorganization-maltreating-families. Published: November 2009. Accessed April 24, 2024.

Text copied to the clipboard ✓