[Archived] The Prevention of Child Maltreatment: Comments on Eckenrode, MacMillan and Wolfe

Geoffrey Nelson, PhD

Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada

Introduction

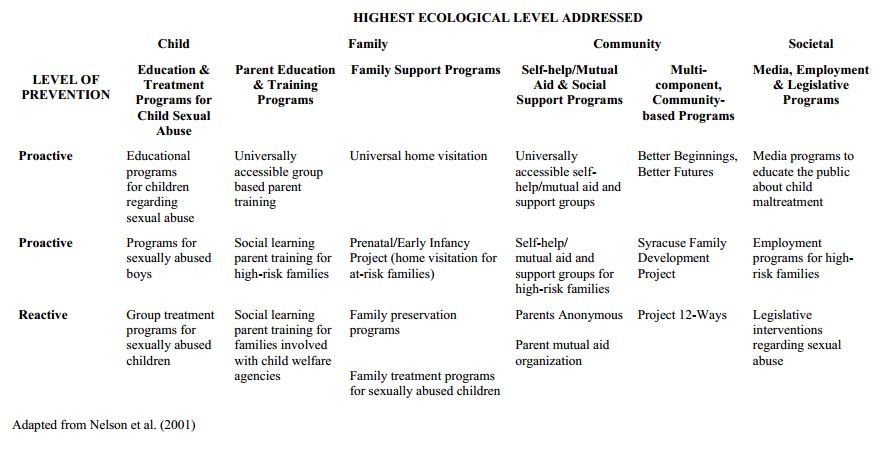

Eckenrode, MacMillan and Wolfe have presented convincing evidence that child maltreatment is an all too prevalent and serious social problem. Eckenrode stated that developmental-ecological and public-health models are the most prominent frameworks for the prevention of child maltreatment. Elsewhere,1 my colleagues and I have integrated these two frameworks with one axis representing the public-health levels of prevention (universal, selective, indicated) and the other axis representing different ecological levels (from micro to macro) addressed by the intervention (see Table 1).

This framework draws attention to three key points. First, it is apparent not only that detection and protection are emphasized over prevention, as noted by Eckenrode, but that most programs are micro-centred, neglecting meso- and macro-level factors.1 Second, in their focus on enhancing protective factors and reducing risk factors, prevention programs not only aim to prevent child maltreatment but also strive to promote the well-being of children, parents and families. Third, in strengthening children, parents and families, such programs are often also successful in preventing a number of other negative outcomes for children, including academic failure, school dropout and criminal behaviour.2 Prevention programs can build strengths and prevent many negative outcomes, not only child maltreatment.

As MacMillan observed, risk and protective factors for child sexual abuse are somewhat different than those for other forms of maltreatment. Moreover, programs for the prevention of child sexual abuse focus on educating children and enhancing their abilities to resist sexual abuse. MacMillan rightly acknowledged the limitations of this approach, which locates the responsibility for prevention with potential child victims rather than with more powerful adult perpetrators. Clearly, more sophisticated theoretical frameworks need to be developed to guide child sexual abuse prevention.

Research

The three reviewers noted the range of different types of child maltreatment prevention programs and asserted that the best evidence that child maltreatment can be prevented comes from studies of home visitation, particularly those by Olds, Kitzman, Eckenrode and colleagues.3,4,5 In a review of this literature,1 home visitation programs that are at least one year in length and provide 20 or more home visits were found to be more effective than shorter and less intensive programs. While there has not been much research on universal media campaigns, one study6 of newsletters for new parents on how to promote infant development reported positive impacts. Parents who received the newsletter scored significantly lower on a measure of child abuse potential and reported spanking or slapping their child half as much in the week prior to the assessment than parents in the control group who did not receive the newsletter.

There are a number of community-based, multi-component prevention programs that provide family support, such as home visitation or parent training, preschool education for children, and a range of other services. While these programs have been found to have larger impacts on child and family well-being than home visitation or media programs7 and thus would seem to have great potential for the prevention of child maltreatment, only one of these programs has examined impacts on rates of child maltreatment. A long-term follow-up of over 1,400 children8 found that children who participated in the Child Parent Centers that provided preschool and school enhancements for children and promoted parent involvement had significantly lower rates (5%) of court petitions for child maltreatment by age 17 than children in a comparison group (11%). Moreover, parent involvement in the children’s school and school mobility were significant mediators of these impacts.

The reviewers are correct in asserting that there is little evidence that child sexual abuse education programs actually prevent this problem. However, one study9 found that undergraduate students who had participated in a “good touch-bad touch” program in preschool or elementary school reported significantly lower rates of experiencing child sexual abuse (8%) than students who had not participated in such a program (14%). While the retrospective design is a limitation, this study suggests that this approach may have some preventive potential.

Implications

There are several important implications of the research and action regarding the prevention of child maltreatment. First, as Eckenrode noted, there is a need for better coordination of research and policy. Too often governments embark on a social policy without building in rigorous research that can evaluate the causal impacts of programs. Second, as Wolfe and Eckenrode have suggested, there is a need to examine program processes and outcomes in different cultural contexts. What is successful for preventing child maltreatment with low-income white families in rural New York may be quite different for low-income African-American families in Memphis or Chicago. Moreover, there is a need for cross-national research, as most of the evaluations of child maltreatment have been conducted in the U.S. and may not be generalizable to other nations.

Third, there is a need to ensure that child maltreatment prevention programs are sufficiently powerful to create positive impacts. There is growing evidence that preschool prevention programs for children must be long and intensive to have short-term and long-term preventive impacts.2 In many locales, governments are reluctant or unwilling to provide adequate funding to ensure that evidence-based child maltreatment prevention programs are disseminated and implemented so that there is fidelity to the original program model. For example, once the demonstration grant for the original nurse home visitation program3 in rural New York ended, the local health unit doubled the caseloads of the nurse home visitors, thus diluting the intensity of the program.10 All of the original nurses quit their jobs in reaction to this decision.

Fourth, prevention programs need to begin to address meso- and macro-level risk and protective factors. Eckenrode pointed out the diminution of social capital in North America and the need to restore it. Unless home visitation and multi-component programs are accompanied by community development, housing and employment programs, children will continue to grow up in toxic neighbourhoods that are characterized by high levels of poverty, substandard housing, violence and criminal behaviour. Finally, social policies that have an agenda of social justice and poverty reduction are needed to support children and families more adequately. There are many excellent models of progressive policies in western and northern Europe that could benefit North American children and families.11 More fully implementing prevention programs, community interventions and social policies to promote family well-being and prevent child maltreatment will require a fundamental shift in social values in North America – from individualism and victim-blaming to collective well-being, support for community structures and social justice.12

Table 1

Examples of Programs for Prevention or Early Intervention of Child Maltreatment by Level of Prevention and Highest Ecological Level Addressed

References

- Nelson G, Laurendeau, M-C, Chamberland C, Peirson L. A review and analysis of programs to promote family wellness and prevent the maltreatment of preschool and elementary school-aged children. In: Prilleltensky I, Nelson G, Peirson L, eds. Promoting family wellness and preventing child maltreatment: Fundamentals for thinking and action. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press; 2001.

- Nelson G, Westhues A, MacLeod J. A meta-analysis of longitudinal research on preschool prevention programs for children. Prevention and Treatment 2003;6:article 31. Available at http://journals.apa.org/prevention/volume6/toc-dec18-03.html. Accessed May 3, 2004.

- Olds DL, Henderson CR, Chamberlin R, Tatelbaum R. Preventing child abuse and neglect: A randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics 1986;78(1):65-78.

- Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, Sidora K, Morris P, Pettitt LM, Luckey D. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: 15-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 1997;278(8):637-643.

- Kitzman H, Olds DL, Henderson CR, Hanks C, Cole R, Tatelbaum R, McConnochie KM, Sidora K, Luckey DW, Shaver D, Engelhardt K, James D, Barnard K. Of prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses on pregnancy outcomes, childhood injuries, and repeated childbearing: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 1997;278(8):644-652.

- Riley D, Salisbury MJ, Walker SK, Steinberg J. Parenting the first year: Wisconsin statewide impact report. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 1996.

- MacLeod J, Nelson G. Programs for the promotion of family wellness and the prevention of child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse and Neglect 2000;24(9):1127-1149.

- Reynolds AJ, Robertson DL. School-based early intervention and later child maltreatment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Child Development 2003;74(1):3-26.

- Gibson LE, Leitenberg H. Child sexual abuse prevention programs: Do they decrease the occurrence of child sexual abuse? Child Abuse and Neglect 2000;24(9):1115-1125.

- Schorr L. Within our reach: Breaking the cycle of disadvantage. Toronto, Ontario: Doubleday; 1988.

- Peters RDev, Peters JE, Laurendeau, M-C, Chamberland C, Peirson L. Social policies for promoting the well-being of Canadian children and families. In: Prilleltensky I, Nelson G, Peirson L, eds. Promoting family wellness and preventing child maltreatment: Fundamentals for thinking and action. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press; 2001.

- Prilleltensky I, Nelson G. Promoting child and family wellness: Priorities for psychological and social interventions. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 2000;10(2):85-105.

How to cite this article:

Nelson G. [Archived] The Prevention of Child Maltreatment: Comments on Eckenrode, MacMillan and Wolfe. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. MacMillan HL, topic ed. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/maltreatment-child/according-experts/prevention-child-maltreatment-comments-eckenrode-macmillan-and. Published: July 2004. Accessed April 25, 2024.

Text copied to the clipboard ✓