New Directions in Home Visiting Research: The Precision Paradigm

1Jon Korfmacher, PhD, 2Anne Duggan, ScD, 3Kay O’Neill, MS

1Chapin Hall at University of Chicago, 2,3Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, USA

Introduction

Early childhood home visiting has policy and programmatic support for the past fifty years as a strategy to promote child health and well-being. During this time, the traditional research paradigm has been to conduct randomized trials to estimate the average effects of full home visiting models.

This research has produced enough positive findings to form an evidence base that supports investment in the scale up of home visiting and for designating specific models in which to invest.1 Such an evidence-based approach has been used for many initiatives, including the U.S. federally funded Maternal Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program (MIECHV) and the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) initiative. But in all fields, research methods must evolve to meet needs for new knowledge.

Subject

In the United States (as well as other contexts), home visiting has largely existed in the form of overall program models comprising a package of supports to parents. Home visiting models attempt to cover many different aspects of family and child functioning that can ultimately impact health, development, and well-being. These models typically articulate elements of program infrastructure, home visitor qualifications, program content and curricula, and visiting schedules.

Problems

Empirical research confirms generally positive overall home visiting effects on many outcomes, but also reveals enduring challenges. One challenge is the persistently small average effect sizes seen in many different randomized trials. The most recent national evaluation of MIECHV-funded home visiting models is an example of this, with effect sizes ranging from 0.01 to 0.09.2 Another challenge is engaging and keeping families in services. Many families leave services after relatively short periods of time, which can be problematic for models with expectations of working with families over a number of years.3

As a result, enrolled families vary considerably in their exposure to home visiting services, which themselves cover many different elements of child and family functioning and serve heterogenous populations and communities. But our research has not done well in unpacking this variability nor in comparing the effectiveness of specific interventions within models and across diverse subgroups of families and communities. We have not yet identified which interventions within multi-faceted home visiting services are effective and whether effectiveness of specific intervention components generalize across models.4

Research Context

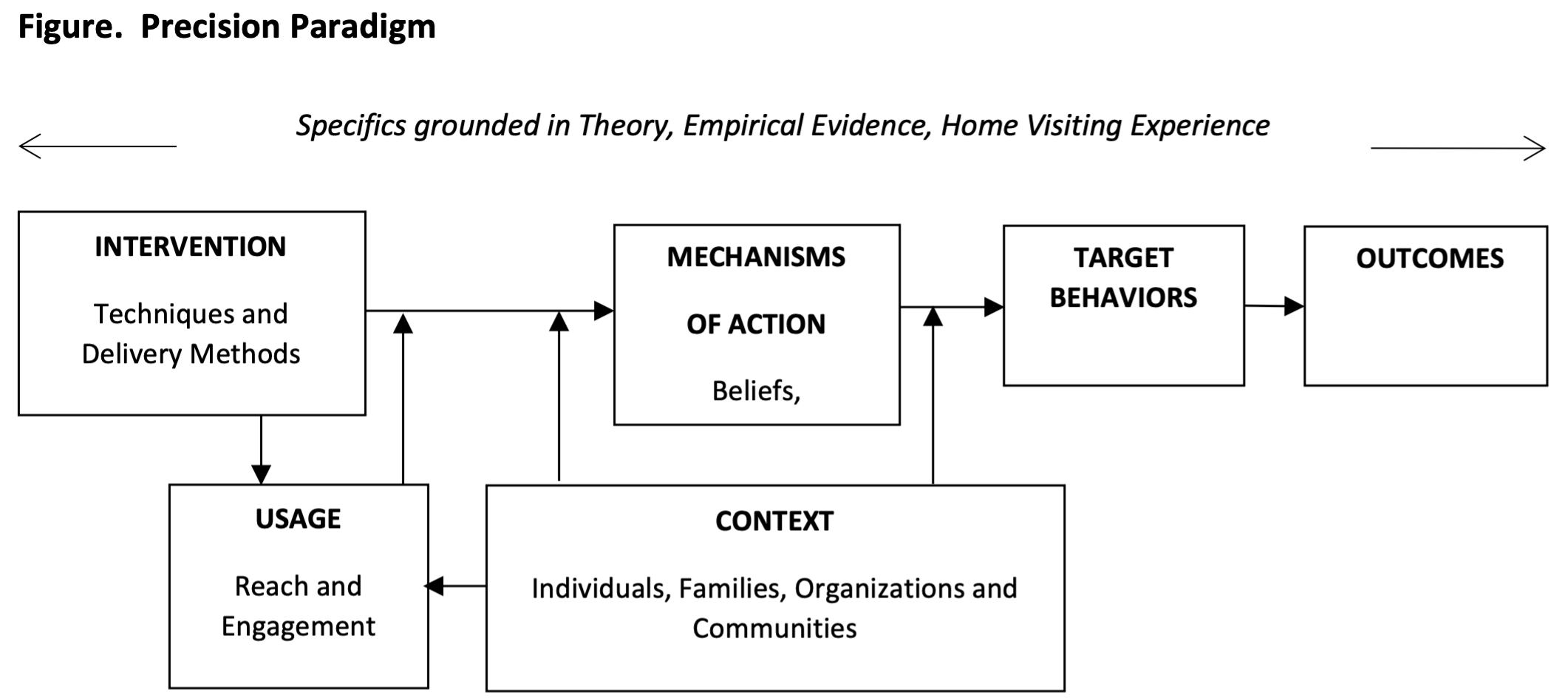

Shifting this paradigm requires building the field's capacity to test the mediators and moderators of interventions within home visiting. The Home Visiting Precision Paradigm, illustrated in the figure below, provides a framework for such research. The Home Visiting Applied Research Collaborative (HARC), a national research and development platform to improve the practice of early childhood home visiting,5 has developed this paradigm, based on frameworks created to categorize efforts at human behaviour change.6

The Precision Paradigm specifies how change is expected to occur by first defining intended program outcomes, mechanisms of action and target behaviours to improve those outcomes. It promotes designs to test the effects of specific intervention techniques and methods of delivery on these mechanisms of action and through these, on target behaviours. Beyond this, it incorporates the effects of context and intervention usage as moderators of intended impacts. A primary interest is on the mediators of impacts on outcomes. For example, if a home visitor provides information on the importance of early development, this may shift the parent’s knowledge in a way that promotes positive parent-child interaction and, ultimately, positive child development. But if this information is not relevant to the parent (e.g., a parent’s stress level does not allow them to attend to this information), then increased child development knowledge will not lead to improved parenting behaviour. The Paradigm drills down to the specifics of what home visitors do and how their actions are intended to lead to short-term changes that prior research has demonstrated will lead to achieving intended outcomes.

Key Research Questions

In simple terms, the new paradigm is designed to answer the question, What interventions within home visiting work best, for which families, in which contexts, why and how?7 It is a useful framework for addressing many related questions, including:

- How clearly defined are the interventions that home visitors are expected to implement?

- How well do implementation systems support home visitors in their interventions?

- How are home visitors expected to modify interventions in light of family and community factors, and how well does actual practice align with these expectations?

Recent Research Results

Emerging studies include a precision-based approach. One recent study focused on how home visiting program models aim to promote positive birth outcomes.8 Representatives of five evidence-based models defined their models' target behaviours to promote good birth outcomes and their expectations for home visitors' use of 23 categories of behaviour change techniques to promote parent's engagement in these target behaviours. Model representatives defined many different pathways and saw most as compatible with their model, but varied in the number required or recommended, as well as in the relative emphasis given to specific home visitor techniques. The short answer from this study emphasizes variability, but it also suggests common ground for more sophisticated cross-model analyses of how home visitors provide support in prenatal home visiting.

Other precision-based research has examined how home visitors using the Family Spirit program model select different modules when working with different sub-populations of families. The modular approach was developed in collaboration with local tribal stakeholders and program implementers to ensure relevance,9 with a trial is currently in progress comparing this approach against a conventional delivery of the program model that does not tailor services.10

Research Gaps

Shifting from a focus on comprehensive home visiting models to their underlying components is not an easy task. Defining active ingredients in specific, testable ways will be an ongoing challenge. Implementation has valued fidelity to models deemed evidence-based by previous examinations, and we have not yet determined the best way understand tailoring in the context of fidelity efforts, nor has traditional reporting of program implementation in efficacy trials been of much help.11 Much previous work looking at moderating factors has relied on post-hoc subgroup analyses and correlational examinations within a treatment group, not systematic comparisons of different combinations of techniques or delivery mechanisms. Modern analytic techniques, such as the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST), are just beginning to make their way into home visiting research.12

Conclusions

Precision home visiting — evidence-based tailoring of services — a granular approach in the design and testing of interventions within home visiting. It requires a solid understanding of how features of interventions influence usage, and how context moderates this usage and the intended links from intervention to outcomes. Early research using the Precision Paradigm is demonstrating proof of concept: home visiting stakeholders can focus on interventions within models and can define intended pathways from intervention to mechanisms of action to target behaviours. Thus, the Precision Paradigm provides a framework for research to specifically test whether and how variation in contextual factors influences usage and impacts on mediators. This knowledge can be used to refine interventions to broaden and strengthen impacts across diverse families and communities. This in turn can accelerate achievement of population-level improvements in outcomes and health equity and can further address disparities in social determinants of health.

Implications for Parents, Services and Policy

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, programs have had to innovate to creatively maintain outreach to families, including virtual methods of service delivery. This further highlights the importance of attending to what home visitors are expected to do and how they might broaden and strengthen home visiting impacts through evidence-based tailoring of what they do. Because of these constantly changing circumstances, understanding the lived experiences and perspectives of stakeholders is essential in order to develop equitable, effective programs. Researchers must create partnerships with programs in order to design more precise evaluations, but also strive to capture the voices of the communities (including families) at each phase of the evaluations.13

In short, precision home visiting can lead to services that are more closely aligned with family preferences and needs, resulting in greater benefit in intended outcomes most relevant to them. Precision will lead to more clarity in job expectations for home visitors and to more coherent implementation systems. This precision can be felt at the policy level as well, as we shift from a focus on evidence-based models to the evidence-based components within them.

References

-

Sama-Miller E, Akers L, Mraz-Esposito A, Avellar S, Paulsell D, Del Grosso P. Home visiting evidence of effectiveness review: Executive summary. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC. 2018.

-

Michalopoulos C, Faucetta K, Hill C, Portilla X, Burrell L, Lee H, Duggan A, Knox V. Impacts on family outcomes of evidence-based early childhood home visiting: Results from the Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation. OPRE Report 2019-07. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2019.

-

Ammerman RT. Commentary: Toward the next generation of home visiting programs—New developments and promising directions. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 2016;46(4):126-129. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2015.12.010

-

Supplee LH, Duggan A. Innovative research methods to advance precision in home visiting for more efficient and effective programs. Child Development Perspectives 2019;13(3):173-179. doi:10.1111/cdep.12334

-

Duggan A, Minkovitz C, Chaffin M, Korfmacher J, Brooks-Gunn J, Crowne S, Filene J, Gonsalves K, Landsverk J, Harwood R. Creating a national home visiting research network. Pediatrics 2013;132 Suppl 2:S82 -S89. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-1021F

-

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP, Cane J, Wood CE. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2013;46(1):81-95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

-

Korfmacher J. Balancing rigor with complexity in understanding the impacts of child maltreatment prevention programs. Prevention Science 2019;21(1), 47-52. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01079-1

-

Duggan AK, Bower KM, Zagaja C, O’Neill K, Daro D, Harding K, Ingalls A, Kemner A, Marchesseault C, Thorland W. Changing the home visiting research paradigm: models’ perspectives on behavioral pathways and intervention techniques to promote good birth outcomes. BMC Public Health. In press.

-

Haroz EE, Ingalls A, Wadlin J, Kee C, Begay M, Neault N, Barlow A. Utilizing broad-based partnerships to design a precision approach to implementing evidence-based home visiting. Journal of Community Psychology 2020;48(4):1100-1113. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22281

-

Ingalls A, Barlow A, Kushman E, Leonard A, Martin L, Team PFSS, West AL, Neault N, Haroz EE. Precision Family Spirit: a pilot randomized implementation trial of a precision home visiting approach with families in Michigan-trial rationale and study protocol. Pilot and Feasibility Study 2021;7(1):8. doi:10.1186/s40814-020-00753-4

-

Supplee LH, Ammerman RT, Duggan AK, List JA, Suskind D. The Role of Open Science Practices in Scaling Evidence-Based Prevention Programs. Prevention Science 2021 Nov 15. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01322-8. Epub ahead of print.

-

Guastaferro K, Strayhorn JC, Collins LM. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) in child maltreatment prevention research. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2021;30(10):2481-2491. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-02062-7

-

Home Visiting Applied Research Collaborative. The importance of participatory approaches in precision home visiting research. December 2018. Available at: https://www.hvresearch.org/additional-resources/#briefs. Accessed January 12, 2022.

How to cite this article:

Korfmacher J, Duggan A, O’Neill K. New Directions in Home Visiting Research: The Precision Paradigm. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Spiker D, Gaylor E, topic eds. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/home-visiting/according-experts/new-directions-home-visiting-research-precision-paradigm. Published: January 2022. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Text copied to the clipboard ✓