What Young Children and their Families Need for School Readiness and Success

Charles Bruner, PhD

Child and Family Policy Center, USA

, Rev. ed.

Introduction

Parents are their children’s first and most important teachers… and their first and most important nurses, coaches, safety officers, nutritionists and moral guides. They also are their children’s first and most important advocates and care coordinators. Most parents, most of the time, are able to fulfill these roles, identifying and coordinating appropriate, affordable services (such as child care and health care) and voluntary supports and activities (such as library visits and recreation and playtime programs) for their children. But there remain far too many instances where parents cannot find or afford the health, education and social services their children need, or the services they locate do not actually meet the children’s needs. Some parents live in neighbourhoods that lack places where young children can play and explore the world safely; other parents are isolated from voluntary supports as well as education and health services. This may be because they themselves are struggling simply to get by and are not connected to voluntary networks or support systems or their neighbourhoods do not have those supports, including playgrounds and family-friendly social activities. Increasingly, research has pointed to the centrality of such supports to healthy young child development – sometimes referred to as “protective factors.”1 And there are far too many children whose parents are not able to fulfill the advocacy and care coordination roles without help. This recognition has given rise to efforts to develop integrative “two generation strategies”2 as well as child-specific ones to foster healthy child development – physical, cognitive, social, and emotional/behavioural.

Problems and Context

These problems are compounded when families or their children have a variety of needs. When children are seen by multiple providers, they and their families may receive mixed and even conflicting direction, at best limiting service effectiveness and at worst adding to families’ confusion, frustration and distress. Researchers have argued for some time that early childhood development services – whether provided through early childhood education programs, health care, family support services, or a variety of specialized counseling and support services for children with special needs – need to be part of a larger, better integrated system. This is particularly true for children with special health care needs that require professional services to address them. Ironically, these services may place new stresses on the parents and children that must be mitigated to create as normalized a home environment as possible.3

Service providers and policymakers have been initiating and adjusting their work in the early childhood arena to develop such a cohesive system. However, it is also important that these questions about integration occur in a larger context, one that considers overall availability of supportive services, and the broader community in which services – integrated or not – are provided.

Recent Research Results

Research is clear that a child’s readiness for school and subsequent school success is dependent upon physical, social, emotional and cognitive well-being and development, and that these dimensions of school readiness are interrelated.4,5 A child with dental pain cannot concentrate fully and is likely to act out. A child with an untreated learning disability is likely to struggle socially and emotionally as well as cognitively. A child whose parent suffers from mental illness is less likely to receive the nurturing needed to foster resiliency and development across all the dimensions of school readiness.6 Parents who are living in poverty and in a marginal or unsafe community may be expending additional time and their own resources simply trying to get through the day, with little in reserve to seek out new opportunities for development for their children.7 Children who start school behind their peers on more than one dimension of school readiness are at much greater risk of falling further behind; and children are rarely behind on only one dimension.8 Up to half of future school problems are already evident by the time children start school.9

When children need services in multiple areas, an aligned, coordinated response produces the best results. Exemplary programs suggest that primary-care practitioners who screen for and make effective referrals to developmental services reduce developmental delays among children.10,11 When focused upon the parent as well as the child, they also can improve parent-child relationships and children’s healthy development across physical, cognitive, social, and behavioural development.12 Early care and education programs with access to mental-health consultants improve children’s emotional and cognitive development and reduce preschool expulsions.13,14

Further, programs and their frontline practitioners that build on strengths, validate parents through developing relationships with them, and support parents in their roles, have proved effective in improving parent-child bonding, family stability, and general nurturing that is at the heart of children’s healthy development.15 Research is clear on the need for an ecological, life-course approach to closing current school readiness gaps – one that addresses the child in the context of family, and the family in the context of community.16 Discrete services such as clinical heath care or preschool can achieve gains that produce positive returns on investment for society, but individually they can only reduce school readiness gaps by a small amount.9 Ultimately, improving children’s health and well-being involves effective professional services and available voluntary supports that are developmentally appropriate and support and strengthen resiliency and reciprocity for young children and for their families through positive social connections – actions that go much beyond discrete, individual service provision.17,18

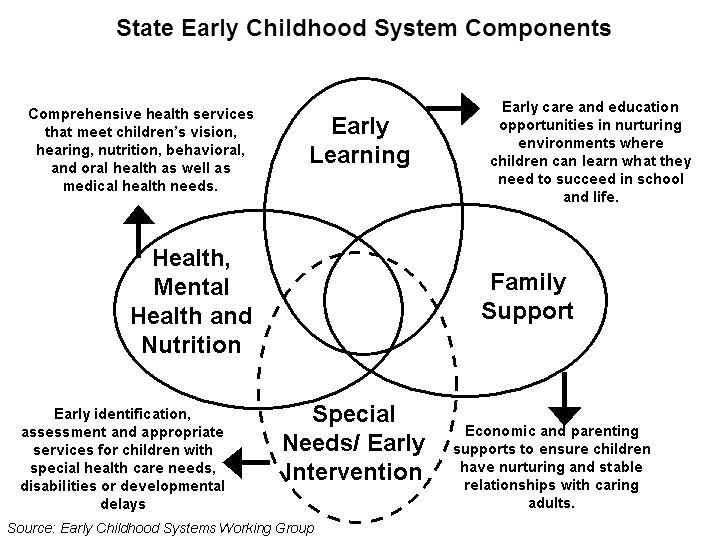

The Early Childhood Systems Workgroup, composed of national leaders from policy and research organizations in the United States, has established a common conceptual framework that recognizes the need for a systemic approach to early childhood development, depicted in the figure below.19

Services in each of the four components, or ovals, must be available, affordable, of good quality and accessible to all who need them. Their overlap stresses that the providers in each oval must be able to connect young children and their families to services outside their professional purview, coordinate with other providers when they are serving the same child and family, and help other providers play an appropriate role in responding to children’s needs across the dimensions.

While a systemic framework, the model does not imply that better coordinating responses across the four components – e.g., integrating systems – is the sole or even the primary need to improve children’s school readiness. For some young children and their families, there may not be affordable, accessible and high-quality services within one or more of the components to address the child’s unique and special needs. Some children do not have access to primary and preventive health services, and many families struggle to find consistent, developmentally appropriate child care for their children.

Even when services are available, families may not be equipped to navigate them or effectively advocate for their children. This can be due to economic circumstances, stress, isolation, family or community violence, mental illness, drug involvement, or lack of parenting confidence and competence. Such family and neighborhood factors, often referred to as social determinants, account for the greatest share of the gaps children experience at the time of school entry.9 Successful strategies to engage and support these families extend beyond professional-to-client services.20 In many respects, this involves population-based or public health approaches that strengthen the overall fabric of voluntary supports for young children and their families (parks, family place libraries, recreational programs opportunities, parent support groups, cultural celebrations and events), based upon an “if you build it, they will come” policy direction that goes beyond discrete service approaches matched to individual children.21

The emphasis upon early childhood systems-building has resulted in cross-agency planning and governance structures at both the state and community level designed to reduce fragmentation and better integrate services. These efforts often concentrate on developing protocols or agreements across systems that reduce barriers to coordinating services, including sharing information. Policymakers, in particular, are eager to know what governance structures produce the best results; significant attention has been directed toward describing and evaluating these governance structures.22 However, research also needs to start at the level of the young child and family, to determine how changes within frontline systems can boost young children’s healthy development.

Research Questions and Gaps

In addition to helping develop the Workgroup’s conceptual framework, the Build Initiative has established an evaluation framework for examining systems-building. (The Build Initiative is a project of the Early Childhood Funders Collaborative, composed of national, regional and state foundations focusing upon early childhood, supporting state efforts to build comprehensive early childhood systems.) This framework recognizes that different evaluation methodologies are needed to examine different aspects of systems-building. In particular, it distinguishes between evaluation of system “components” and system “connections.”23 The former generally involves program-evaluation methodologies, which have been the primary focus of early childhood development research. The latter involves evaluations of cross-system linkages, which have been subject to very little empirical analysis. To this can be added voluntary, publicly available supports.

Evaluating cross-system linkages and voluntary supports both require a different focus than traditional program evaluation. They require examining cohorts of young children, often identified by place as well as service provision, their involvement with services, and their resulting trajectories of growth and development. These examinations could start with young children coming to the attention of a particular program or they could start from a universal event (birth) or population base (all young children in a certain neighborhood). Research questions regarding these connections include:

- At what point did any service provider identify needs of the young child and family that fell outside of that provider’s capacity to respond?

- What did the provider do to help the young child and family to secure that response elsewhere, and were those actions successful?

- When more than one service provider was involved, was their work aligned and coordinated and did it respond to multiple needs?

- What strategies produced good connections across services, and what were the reasons for poor connections?

- Did the presence of additional voluntary services and supports result in both greater use of those services and supports by otherwise disconnected families, and did these have a stabilizing or cohesive role in making he overall environment supportive of all young children and their families?

- Ultimately, did the child start school healthier and better equipped for success as a result of an integrated response to his or her needs?24

Actual methodologies include action research, comparative case study review, and, as efforts move from the qualitative to the quantitative, content analysis and goal attainment scaling, including results mapping.25

Clearly, the Workgroup’s conceptual framework makes theoretical sense for analyzing what young children need to succeed and what public policies can do to support them. Yet it remains a framework and not a theory of change, with testable assumptions.26,27 It does not provide any assessment of the relative importance of strengthening connections versus building strong individual programs versus creating greater economic security for families or more young child-friendly neighbourhoods. Depending upon the child, the community and the array of existing services, that assessment may produce different answers.

Clearly, better coordination across overwhelmed systems is unlikely to produce much gain. If services are accessible only to those with the persistence and resources to secure them, they may help individual children but not meet social needs as a whole. In short, integrated services at best are an answer to only some of the challenges that face young children and their families.

Conclusions and Implications for Parents, Services and Policy

The following research question should be added to those stated before and may well be the most important one to address:

- What did families identify as their young children’s needs in the context of their hopes for their children, how were families involved in ensuring those needs were met, and to what extent did they feel their children received the help they needed?

No matter how well integrated, public programs cannot ensure the healthy development of vulnerable young children by taking actions without the involvement of or in spite of their families. Services and supports need to start where families are, not where systems would like them to be. One study of families involved in multiple systems found those families to be as frustrated by the lack of consistency of support within systems (as their case managers and workers frequently changed) as across them, and what they most needed often was not addressed by any system. Indeed, parents were generally more knowledgeable of what different systems provided than the workers who offered referrals.28

Moreover, there is a strong research base for a relationship-based approach that builds upon family strengths and goals and does not solely look to reduce deficits or meet needs. This approach is particularly noted in the family support, resiliency, and reciprocity literature.29 Research, common sense and societal values all speak to young children needing and deserving consistency and continuity in their nurturing, supervision and protection. Public and professional services – in health, early learning, family support and special needs – should be coordinated and integrated to ensure they contribute to producing that consistency and continuity. The danger is to define the lack of coordination and integration as the cause for children’s school unreadiness and success and direct sole attention there, where there may be other, much more important gaps, policies or practices that need to be addressed, not the least of which is focusing upon opportunity and virtually all parents’ hopes that their children succeed.

References

- Browne C. The strengthening families approach and protective factors framework. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2014.

- Kids Count. Creating opportunity for families: A two generation approach. Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2014.

- Bethell C, Peck C, Abrams M, Halfon H, Sareen H, Scott Collins Kl. Partnering with parents to promote the healthy development of young children enrolled in Medicaid: Results from a survey assessing the quality of preventive and developmental services for young children enrolled in Medicaid in three states. Commonwealth Fund. September 2002.

- Shonkoff J, Phillips D, eds. From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Research Council: Institute of Medicine; 2000.

- Shepard L, Kagan SL, Wurtz E, eds. Principles and recommendations for early childhood assessments. Washington, DC: National Education Goals Panel; 1998.

- Knitzer J, Theberge S, Johnson K. Reducing maternal depression and its impact on young children: Toward a responsive early childhood policy framework. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2008.

- Bruner C. ACE, Place, race, and poverty: Building hope for children. Academic Pediatrics 2017;17(7S):S123-S129.

- Halle T, Forry N, Hair E, Perper K, Wandner L, Wessel J, Vick J. Disparities in early learning and development: Lessons from the early childhood longitudinal study – birth cohort (ECSL-B). Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers and Child Trends; 2009.

- Rouse C, Brooks-Gunn J, McClanahan S. Introducing the issue: School readiness: Closing racial and ethnic gaps. The future of children 2004;15(1):5-14.

- Bruner C, Schor E. Clinical health care practice and community building: Addressing racial disparities in healthy child development. Des Moines, IA: National Center for Service Integration; 2009.

- Center for Prevention and Early Intervention Policy. Mental health consultation in child care and early childhood settings. Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University; 2006.

- Bruner C, Dworkin P, Fine A, Hayes M, Johnson K, Sauia A, Schor E, Shaw J. Trefz MN, Cardenas A. Transforming young child primary health care practice: building upon evidence and innovation. Child and Family Policy Center. 2016.

- Gilliam W. Prekindergarteners left behind: Expulsion rates in state prekindergarten programs. New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development; 2005.

- Brofenbrenner U. Ecology of the family is the context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology 1986;22(6):723-744.

- Kagan S, Weissbourd B. Putting Families First: America’s Family Support Movement and the Challenge of Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishes; 1994.

- National Research Council. Committee on Evaluation of Children’s Health. Children’s health, the nation’s wealth: Assessing and improving child health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

- Horton C. Protective factors literature review: Early care and education programs and the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC; Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2003.

- Bruner C. Philanthropy, advocacy, vulnerable children, and federal policy: Three essays on a new era of opportunity. Des Moines IA; National Center for Service Integration; 2009: 57-65.

- Bruner C. Building a coordinated and comprehensive state early childhood system: A framework for state leadership and action. Portland, MN: Build Initiative; 2010.

- Bruner C. Village building and school readiness: Closing opportunity gaps in a diverse society. Des Moines, IA; State Early Childhood Policy Technical Assistance Network; 2007.

- Pinderhughes H, Davis R, Williams M. Adverse community experiences and resilience: a framework for addressing and preventing community trauma. Oakland CA: Prevention Institute; 2015.

- Bruner C, Stover-Wright M, Gebhard, B, Hibbard S. Building an early learning system: The ABCs of planning and governance structures. Des Moines, IA; State Early Childhood Policy Technical Assistance Network and Build Initiative; 2004.

- Coffman C. A framework for evaluating systems initiatives. Portland, MN: Build Initiative; 2007.

- Bruner C. Developing an outcome evaluation framework for use by family support programs. In Dolan P, Canavan J, Pinkerton J, eds. Family support as reflective practice. London, GB: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006.

- Kibel B. Success stories as hard data: An introduction to results mapping. New York, NY: Kluner Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999.

- Weiss C. Nothing as practical as good theory: Exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In: Connell J, Kubisch A, Schorr L, Weiss C, eds. New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: Concepts, methods, and contexts. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute; 1995: 65-92.

- Mills C, Gitlin T. The sociological imagination. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Cameron M, Bruner C. Through the eyes of the family. Des Moines, IA; Child and Family Policy Center; 2000.

- Pattoni L. Strength-based approaches for working within individuals. Insight 16. https://www.iriss.org.uk/resources/insights/strengths-based-approaches-working-individuals. Published May 2012. Accessed March 2019.

How to cite this article:

Bruner C. What Young Children and their Families Need for School Readiness and Success. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Corter C, topic ed. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/integrated-early-childhood-development-services/according-experts/what-young-children-and-their. Updated: March 2019. Accessed March 4, 2026.

Text copied to the clipboard ✓